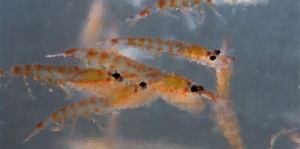

“In the Antarctic, krill, which means ‘whale food’ in Norwegian, sustain not only whales, but also penguins, seals, squid, fish, albatross, and other seabirds. These small, shrimp-like creatures represent the very cornerstone of the Antarctic ecosystem — processing the energy of the sun stored in phytoplankton (microscopic free-floating plants) and breeding by the thousands to provide an abundant source of nourishment for higher-order predators. Virtually all the larger animals of the Antarctic are either directly or indirectly dependent on krill.” – from Krill: Cornerstone of the Antarctic, PBS.org

From my journal:

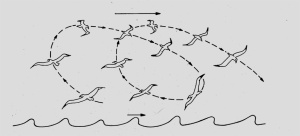

“Chinstrap Penguins at Bailey Head stream up the slopes in a continuous river of movement: swirls of penguins, freshets of penguins, long sweeping arcs of penguins, occasional eddies of penguins that hesitate briefly before continuing on.

I point the viewfinder of my video camera into this chaos of penguins, then zoom in to focus on a square meter of black sand. I can cope with this small patch, analyze it just as I would a fluid flow problem. Establish a fixed reference volume and measure what goes in, what goes out. Thirty-eight penguins pass through my little box in two minutes. That’s nineteen penguins per minute per meter. The penguin stream here is about six meters wide. One hundred and fourteen penguins per minute passing this point, flowing uphill, uphill. Uphill to the chicks.

I change experimental techniques. One can also study flowing fluids by tracking the path of individual particles within the flow. I pan the camera back to the source of penguins, the rolling swells at the beach. Catch a knot of penguins at the water’s edge. Choose one. Watch the swell sweep it up onto the beach. It stands erect and steps. Step, step, step. Halt. Shake. Joins the flow: step, step, step. The penguin particle traces a path, a penguin streamline, up the beach toward the colony.

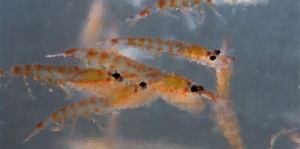

At this time of day, the net flow of penguins is uphill. Occasionally individuals or small groups can be found bucking the tide, going down toward the sea. Perhaps one in forty, one in fifty. Also going down the hill is a small stream of fresh water. The sea below penguin colonies seems always to be tinted, muddy, reddish, murky with suspended sediments of earth and guano: guano dyed pink with krill colors, organic krill dyes.

Krill fuel this system, provide the energy that pushes this flow of penguins uphill in defiance of gravity. Step, step, step. Each footstep like a meshing gear tooth in a machine. Lifting krill soup, krill stew. Kilocalories of krill being carried up in discrete penguin packets, levered up the hill step by step.

I first sit on the sand, then move to a rock further up the slope. I use my brain as a signal processor, filtering out the squawks, creaks and groans of penguin vocal cords. Filter out the rolling swish of water onto the beach. I focus on the background sound, the stepping sounds, the almost sibilant slapping of feet onto the ground. Step, step, step. The quiet, insistent background sound of energy going uphill, always uphill.

I go with the flow. Climb the hill myself. The stream of penguins opens, parting to form a tear-drop shape of penguin-less space around me, as if I were a boulder in the stream. As I top the hill the stream begins to lose its identity, to diffuse, to disappear into the melee of the colony. Here raucous groups stand in the sun on the rounded slopes above the beach. Chicks beg for food, insistently pecking at adult bills. The chicks are of course the reason for all the commotion, all the movement, all the flowing river of black and white that stretches back across the sand into the distance. The penguins in the distance are barely distinguishable, but their rocking, pendulum-like motion looks like ripples on water, like the fine-grained capillary waves that dapple otherwise calm seas. Each roll, each bob represents a step. Step, step, step. Nearly countless feet taking nearly countless steps, right, left, right, left, a sound like light rainfall. As time passes and my memories of Antarctica fade, I know that it will be the memory of these soft sounds of penguins stepping slowly, steadily up the slopes of Bailey Head that will make this precious moment real for me once again.”

– Roy Beckemeyer, Deception Island, South Shetlands, January 31, 1998.